When one imagines pristine Arizona’s dry, desolate, sunbaked deserts in the 1850s it’s difficult to picture any of it as being a utopian Shangri La but for a brief period, in a beautiful green valley at the foot of the majestic Santa Rita Mountains, there was just such a place.

In his twilight years Charles Poston, recognized today as “The Father of Arizona,” wrote glowingly of it.

“We had no law but love and no occupation but labor, no government, no taxes, no public debt, no politics. It was a community in a perfect state of nature.”

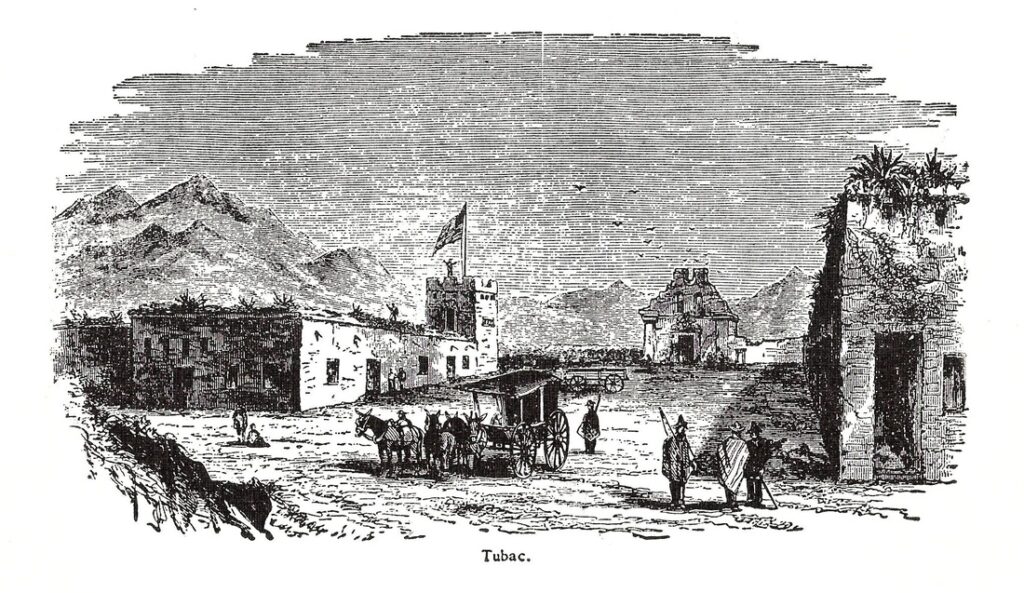

In August 1856, Poston, accompanied by a group of German miners and a brigade of rough-hewn Texas frontiersmen, described as “not afraid of the devil……armed with Sharp’s rifles, Colt revolvers and the recklessness of youth,” arrived in the small pueblo of Tucson. They were on their way to occupy the abandoned settlement of Tubac some fifty miles further up the Santa Cruz River and re-open some of the old mines from the Spanish Colonial Period. He’d explored the mountains west of the river two years earlier and found rich deposits of silver.

The old Spanish presidio was abandoned with all the adobe buildings in disrepair. The first order of business was to get the old pueblo up and running again. The three-story tower was restored and served as a lookout. The armory became a storehouse for supplies. Lumber for construction came from the nearby Santa Rita’s.

The miners found gold in the streams and silver in the mountains. The richest silver mines were in the Cerro Colorado’s where it assayed out at $950 to the ton. One mine assayed at $7,000.

The mining camp bonanza gave a boost to commerce along the entire Santa Cruz River Valley. Skilled miners were paid fifteen to twenty-five dollars a month, a tidy sum for the times. By 1857 the population in the Valley had grown to 3,500. Pack trains from Mexico brought in food staples and French wine from Guaymas. Fruits and vegetables were purchased from the nearby mission at Tumacacori.

Since the Mexicans couldn’t read English, Poston devised a cardboard currency called boletas, to pay their wages. Renderings of animals were used to indicate the value. A pig was worth twelve and a half cents; a calf, twenty-five cents; rooster, fifty cents; horse, one dollar; a bull, five dollars; and a lion was worth ten dollars.

The revolutions in Mexico and the California Gold Rush had depleted the male population in northern Sonora. In some villages the ratio of women to men was twelve to one. This caused a mass exodus of unattached young women who proceeded to head for Tubac. It also became a Gretna Green for young runaway couples who couldn’t afford the twenty-five dollar fee the priest charged them to marry.

Poston, being Tubac’s jefe and by Mexican law that made him the magistrate or the alcalde, (mayor). Poston referred to himself the “El Cadi.” He married the young couples for free and even gave them a wedding present. He baptized their babies and if necessary, granted them divorces.

Of the women, Poston wrote: “Sonora has always been famous for the beauty and gracefulness of its senoritas. They really had a refining influence on the frontiersmen. Many of them had been educated at convents and they were all good Catholics…..They could cook, sew, sing and dance……”

The observant El Cadi also wrote, “They are exceeding dainty in their underclothing, wear the finest linen they can afford.”

The ladies referred to the American men as los goddamies for their propensity to use the term with so much frequency and the few American women were las camiso’s colorados due to their fondness for red petticoats.

They could also give a good account of themselves in men’s games if chance, “….they were expert at cards and divested many a miner his week’s wages over a game of monte”

Alas, Poston’s Utopia was too good to last. The Archbishop in Santa Fe, Jean Baptiste Lamy dispatched Father Joseph Machebeaf to Tubac to check things out.

Shocked at this “perfect state of nature,” Machebeaf immediately declared all the marriages performed by Poston null and void. Naturally, there was much wailing and dismay in Tubac. Something had to be done to quell the crisis so the El Cadi and the padre worked out a deal; Poston would make a charitable donation to the Church and the priest would remarry the anxious couples. Problem solved.